When I was seventeen, I strapped on roller skates for the first time and promptly learned two important truths about life.

One: the floor is not your friend.

Two: your friends are not your friends the second you try something new in public.

Within an hour—an hour!—I could skate in a straight line without eating it. That should have earned me a certificate, a small parade, and at least one commemorative T-shirt. Instead, it earned me relentless mockery, the kind that can only be delivered by teenagers who are still powered by confidence and cafeteria pizza.

But I didn’t care. The moment I stopped wobbling like a newborn giraffe and started gliding—smoothly, cleanly, like the skates and I had come to an agreement—I was hooked. It felt like freedom on eight tiny wheels. Not “freedom” as in a deep philosophical awakening. More like, “Oh wow, my body can do this and it’s fun and I feel like a superhero who smells faintly of rink carpet.”

Not long after that, my mom and I moved from our creaky Victorian house on the edge of the city to a brand-new suburban development. You know the kind: endless streets, pristine pavement, barely a tree tall enough to cast a shadow. It was basically a roller skater’s private runway. A dream track. A nightly invitation.

So I did the only reasonable thing a seventeen-year-old can do when he discovers something that makes him feel alive: I bought a pair of skates and treated the neighborhood like it was my personal training facility.

Every single night, I went out around 10:00 p.m. and stayed out until nearly 2:00 a.m. Yes, you read that correctly. While other people were sleeping, studying, flirting, or committing crimes like “being well-rested,” I was circling cul-de-sacs, carving turns, and flying down streets like my life depended on it.

I skated so much I wore through two full sets of wheels.

That’s not a metaphor. That’s a confession.

I wasn’t just dabbling. I was devoted. I was obsessive. I was the kind of kid who finds a thing and decides it will become his entire personality. Roller skating wasn’t a hobby; it was my nightly ritual, my private religion, my “don’t talk to me, I’m busy becoming excellent” era.

And did I get better?

Oh, hell yes.

By nineteen, I wasn’t just skating in a straight line. I was flipping, spinning, jumping, skating backwards at speed, weaving slaloms like I was auditioning for the roller-disco_toggle?? No. Like I was trying out for the roller-disco Olympics. I was doing tricks that made other people stop and stare. If skates had wings, I would have taken off. I would have been airborne, smiling, smug, and absolutely insufferable about it.

My body back then was built for movement. Not because I was born with some magical athletic gene, but because I treated my body like a playground and a workhorse at the same time. I was trail biking, playing badminton, swimming, skating. I was active in that casual, accidental way you can be when you’re young and your joints don’t file formal complaints after a short flight of stairs.

I had calves that could crush walnuts. Thighs like tree trunks. Balance like a cat. Endurance like a machine. And most importantly, I had the kind of confidence that only comes from believing you are practically indestructible.

Then real life happened. You know, the glamorous stuff.

Work. Responsibilities. Bills. Marriage. The slow, steady accumulation of days where you’re too busy keeping the whole ship afloat to notice you haven’t done the thing you love in months… and then years… and then suddenly it’s a whole different decade and your skates are basically just a memory with laces.

My tiny-wheeled obsession got shoved into the dusty corners of my mind. I didn’t “quit,” exactly. I just… stopped. Like so many things we don’t formally end. We just set them down and never pick them back up.

And I haven’t laced up skates since.

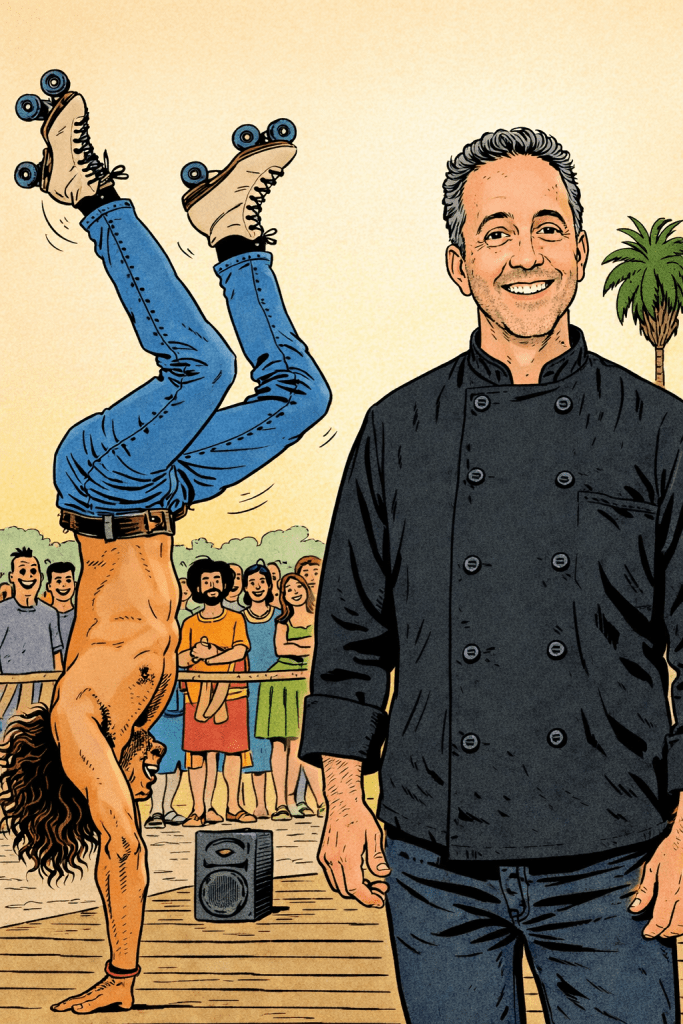

Fast forward to today, and I’m strolling through a beach town. Just walking. Being normal. Pretending I’m not constantly doing an internal inventory of my energy levels like I’m managing a limited budget that could collapse at any moment. The air is salty, the vibe is light, and for a moment I’m almost fooled into thinking I’m a carefree person who doesn’t have to negotiate with his own lungs.

Then I see him.

Some guy on skates.

He’s not just rolling along casually, either. He’s doing one of those jaw-dropping tricks—the kind that makes a small crowd gather. He lands it clean. The crowd gasps like they’re watching a miracle. People clap. Someone says, “Oh my God!”

And my first instinct—my immediate, uninvited, wildly confident first instinct—is to shout: “I could do that! Better!”

Not out loud. I’m not a monster. But in my head? I was already halfway through a performance routine, bowing dramatically to imaginary applause, probably accepting a sponsorship deal from the local ice cream shop.

Because that’s how memory works, isn’t it? It doesn’t just replay the past. It resurrects it. It grabs an old version of you and shoves him into your present-day brain like, “Here you go. Remember this guy? He was amazing. Let’s go be him right now.”

Only… could I really?

Let’s not lie to ourselves.

It has been forty-four years since those wheels touched my feet. Forty-four years. That is not “a little rusty.” That is not “I’ll just warm up and I’ll be fine.” That is archaeological. That is, “We found a relic from the late 1900s and it still thinks it can do backflips.”

And roller skating is not like riding a bike. People love to say that. “Oh, it’s like riding a bike, you never forget.” That’s a nice story we tell ourselves because it’s comforting. But bikes don’t require you to launch your body into the air and rotate it while balancing on four wheels under each foot. Bikes also don’t demand your ankles sign a waiver.

Nineteen-year-old me could do it because I had a nineteen-year-old body. A body that recovered quickly, adapted quickly, bounced back quickly. A body that didn’t come with medication schedules and energy crashes and weird new limitations that show up unannounced like distant relatives expecting a meal.

Now? My legs are still strong, yes. I’m not made of glass. I’m not fragile in the way people sometimes imagine when they hear the words chronic illness. I can do a lot. I’ve learned how to do a lot.

But the sarcoidosis, the heart failure, the medications—they’ve all left their fingerprints.

Some days, walking up a single block of incline can leave my lungs screaming and my heart staging a protest like it’s filing a grievance with HR. Other days, I can manage more and I feel almost normal, almost like I could get away with pretending I’m the guy I used to be.

But skating flips and backward spins? Not happening. Not safely. Not realistically. Not without a complete rewrite of the laws of physics and my cardiologist’s facial expression.

And here’s the part that surprised me: it didn’t break my heart the way I thought it might.

It stung, sure. There was a sharp little pinch of grief. Not dramatic grief, not sobbing-in-the-shower grief. More like the quiet grief of realizing your body has a history. A story. And some chapters are closed.

Because the truth is, there’s a particular kind of sadness that comes with remembering what your body used to do.

It’s not vanity. It’s not ego—well, okay, it’s a little ego. I was really good. Let me have this.

But mostly it’s mourning. It’s a strange, tender mourning for the ease you once had. The trust you once had. The ability to do things without thinking through consequences like you’re planning a military operation.

When you live with chronic illness, your body becomes something you manage. You negotiate with it. You read its signals like weather patterns. You make plans and backup plans and backup-backup plans. You learn that “feeling good” doesn’t always mean you’re safe to push. You learn that a good day can be followed by a bad day for no obvious reason other than your immune system decided to be dramatic.

And you learn that sometimes the hardest part isn’t the physical symptoms. It’s the mental math.

Can I do this today?

Should I do this today?

If I do this today, what will it cost me tomorrow?

Is it worth it?

Will I regret not doing it?

Will I regret doing it?

Watching that skater in the street, I felt all of that in the span of a few seconds. The old confidence flared. The current reality answered. And then something else happened—something I didn’t expect.

I let myself off the hook.

I didn’t stand there berating myself. I didn’t spiral into that familiar trap of comparing my present self to my past self like it’s some kind of contest I’m constantly losing. I didn’t make it mean I was less-than, or broken, or “not who I used to be” in the bitter way people say when they’re trying to make a tragedy out of a life.

Instead, I looked at him—this young guy with his flexible knees and fearless ankles—and I felt something close to joy.

Because I remember that feeling. I remember what it was like to fly.

And I can celebrate what my body used to do without punishing myself for what it can’t do now.

That’s the trick, isn’t it?

Not the backflip. Not the spin. Not the landing.

The real trick is learning to carry your past with affection instead of using it as a weapon against your present.

I can cheer on the young skater in the street. I can clap and smile and feel that little internal bragging voice whisper, “Yes, I once did it better,” because honestly, that voice deserves a tiny moment of glory. He worked hard for those calves.

But I don’t have to prove it.

I don’t have to strap on skates to validate my memory. I don’t have to risk a fall, an injury, a cascade of symptoms, or a cardiac drama just to satisfy the part of my brain that’s still convinced we’re nineteen and invincible.

I can be proud of who I was. And I can be compassionate toward who I am.

And that compassion matters, especially for those of us living with sarcoidosis and other chronic conditions that don’t always show on the outside but absolutely run the show behind the scenes. The world loves a comeback story. The world loves a “mind over matter” narrative. The world loves to tell you that if you just try hard enough, you can do anything.

Sometimes the bravest thing you can do is say, “Actually, no. Not that. Not anymore. And I’m not going to make myself feel like garbage about it.”

Because living well with chronic illness isn’t always about pushing. Sometimes it’s about choosing. It’s about protecting the life you have instead of mourning the life you had so loudly you can’t hear the good parts of the present.

And listen—I’m not pretending this is easy every day. Some days I still get mad. Some days I still have that flash of jealousy when I see someone jogging up a hill like it’s nothing. Some days I miss my old stamina the way you miss a friend who moved away and never calls.

But I’m learning. Slowly. Stubbornly. With plenty of sarcasm.

I’m learning that grief doesn’t have to be dramatic to be real. I’m learning that nostalgia can be sweet without turning sour. I’m learning that the body you have today deserves respect, not constant comparison.

And I’m learning that if I want to feel that old freedom again, I don’t have to recreate it exactly.

Freedom can look different now.

It can look like a slow walk by the water on a day my lungs are cooperating. It can look like cooking something comforting and feeding the people I love. It can look like laughing at my own ridiculous internal monologue. It can look like resting without guilt—resting like it’s a skill, because honestly, it is.

It can look like standing in a beach town, watching a kid fly on skates, and letting myself smile instead of ache.

So tell me—have you ever given up something you loved? Sports, dance, music, skating, running, anything that used to feel like yours? Have you ever seen someone doing it years later and felt that sharp little tug of “I used to…” followed by the heavier thought of “I can’t…”?

If you have, I’d love to hear it. Drop a comment and share what it was, what you miss, and what you’ve learned about your body along the way. And if you want more reflections like this—equal parts heartfelt and mildly annoyed at reality—subscribe so you don’t miss the next one.

Discover more from Tate Basildon

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This letting go is what aging is all about methinks. And you do it gracefully. Thats awakening to the future. Blessing you in your current future.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Selma. Blessing to you also 🤗

LikeLike