There are very few things I dislike in this life. But one of those high up on the list, is Halloween. With every passing year, my dislike of it only deepens, and I think the trouble isn’t just the plastic tombstones lined up in yard-after-yard but what it reveals about us—and me.

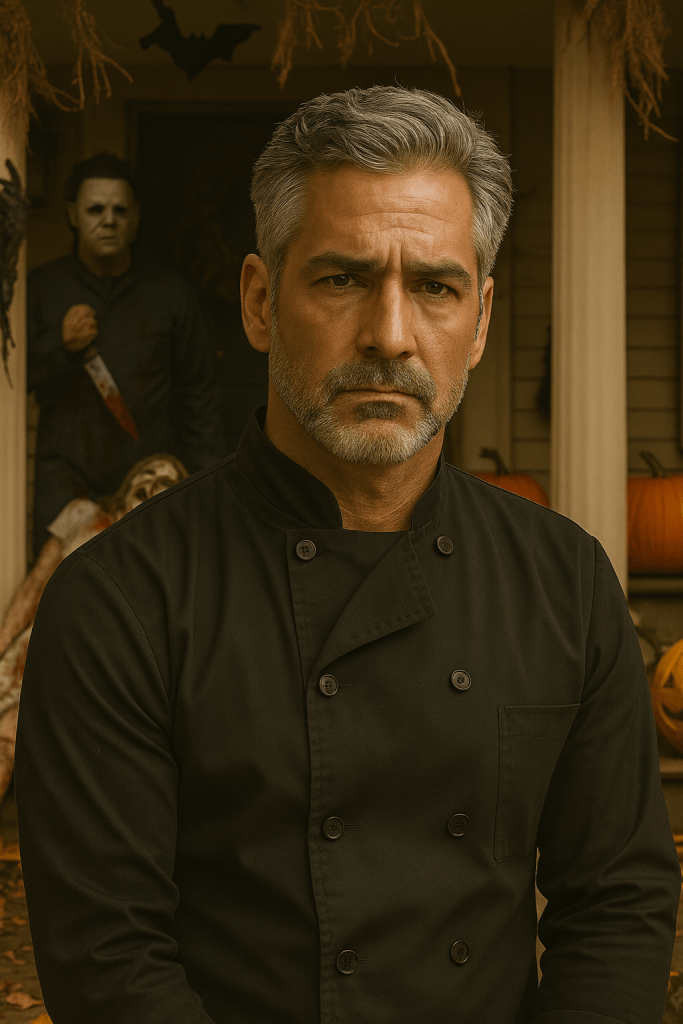

When I first moved to the US, October meant cozy fall: pumpkins perched by doorsteps, hay bales stacked like an art installation, corn-stocks leaning like sentinels. A little ghost decoration here, a plastic skeleton there. Harmless. But over the years something changed. Very slowly at first, then with annoying rapidity. Halloween morphed from ghosts and goblins and vampires (fictional, yes) into serial-killer mannequins stabbing women on lawns (yes, I actually saw this). The boundary between “fun scary” and “did someone really ask for this?” got erased. It’s grotesque. It makes me sick—figuratively, and yes, personally (immune system & heart, remember?).

Here’s the thing: psychology tells us that Halloween has a dark undercurrent. Scholars argue that Halloween—and the suits of decorations, the scary costumes, the ritual celebration of “what’s scary”—are rooted in our human biology and our fear of death. It’s a “safe fear” environment: we allow ourselves the adrenaline rush, the illusions of danger, but ultimately the monster goes back in the closet and we’re fine.

But what happens when that safe fear stops feeling safe? When the decorations celebrate the darkest side of humanity rather than the playful flip of a ghost? When the communal ritual seems less about harvest and more about glorifying violence? I feel it in my bones (actually, I suppose I feel it in my failing heart too): this version of Halloween doesn’t just make me uncomfortable—it triggers a visceral why are we celebrating our worst selves? reaction.

Psychologists talk about what’s called the “terror management theory” — the idea that humans, knowing death is inevitable, build cultural rituals to manage the terror of mortality. Halloween may be one of those rituals. But when the ritual becomes graphic and glorifies death or violence rather than lighting the darkness with a candle, the balance tips. I’m already living with disease, body vulnerability, looming risk. The celebration of our fear of death feels less cathartic, more exploitative.

Another psychological angle: costumes and horror let us play with fear—an imaginary threat, adrenaline, catharsis. I get that. But that requires the sense of safety. It also requires the sense of meaning: you dress up, scare yourself a little, share a laugh, move on. When the scare becomes graphic and the meaning gets lost, it’s just noise. And for someone whose body reminds them daily how fragile life is, Halloween’s “party with gore” version is tone-deaf.

And let’s talk about community. One of the original charms of Halloween was neighborhood gathering, kids in costumes, shared small rituals. Now I drive through streets and see adult-only installations of violence, the trick-or-treating phase (which I actually kind of miss) overshadowed by adult parties and the spectacle of horror. For me, someone whose immune system keeps me at arm’s length from crowds, it feels like a holiday that’s moved past me.

So yes: I’m grumpy about Halloween. Not because I lack a sense of fun—I make my living with fun (recipes, flavors, stories). But because the holiday has shifted in ways that conflict with what I believe: that life is precious, that illness reminds us of fragility, that community matters, that celebrating darkness can be okay if you’re also celebrating light. This version of Halloween? Not so much.

If you might feel this too—maybe a different holiday or ritual hits you wrong for the wrong reasons. The psychology of celebration and fear is real, the biology of adrenaline, amygdala activation, safe exposure to fear—they all exist. And if you’re tired of the gory lawn mannequins and silent costume mass hysteria, know you’re not alone.

In short: I reject Halloween, or at least the version it’s become. I’ll tolerate the pumpkin patches, I’ll smile at the kids’ costumes from a safe distance, but the serial-killer display? Hard pass. Because celebrating the dark side of humanity when you live each day negotiating body pain and fragility… it doesn’t feel celebratory. It feels abrasive.

So if you’re nodding along (“yes, I hate that too”), drop me a comment. If you’re curious about how to navigate holidays while living with chronic illness, or how to write your way through feeling alienated by culture—subscribe, let’s do it together. Because the world of holiday fear-fest may be having its moment—but our lives have bigger, deeper things going on. And we deserve rituals that honor that, not mock it.

Discover more from Tate Basildon

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.