I used to joke that my body got its medical timelines from a senior center newsletter someone accidentally faxed to the wrong house. Back when I wrote the original version of this story in 2010, I was forty-eight, which is young enough to still pretend I understood TikTok dances but old enough to grunt every time I stood up from a couch. Even then, I was dealing with illnesses that typically belong to people who qualify for discounts at diners and have strong opinions about early-bird specials. Heart failure was supposed to be something that visited people in their seventies, not someone juggling a chef’s schedule, sarcoidosis, hospital visits, and a growing collection of pill bottles.

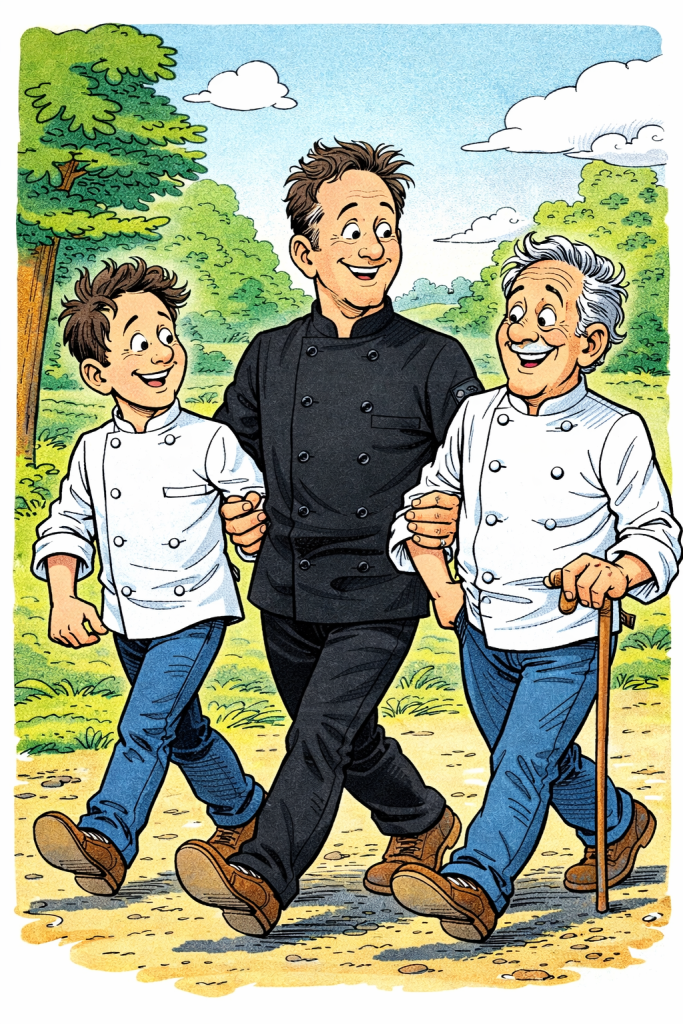

But here I am now at sixty-three, slowly growing into the age group I used to scan for on brochures just to see if anyone looked remotely like me. I’m still not quite the silver-haired grandfather smiling at his cardiologist on the Medtronic website, but I’m getting warmer. These days, when I look at those ads, I don’t think, Who is that old man? Instead it’s more like, Ah yes, one of my people. I used to feel like the baby of the group, the lone kid at the grown-ups’ table of chronic illness. Now I’ve graduated into that strange in-between place: older, seasoned, but still not quite the demographic the medical world expects. A little like being the sous-chef who keeps getting mistaken for the intern.

Back then, every time I looked up heart failure or pulmonary hypertension or COPD, I was greeted by men and women who had at least thirty years on me. They were always smiling in that “Yes, I’m discussing my major organ failure but also enjoying a light lunch afterward” way that only stock photo models can. No matter the website, pamphlet, or medication ad, the stars of the show were retirees in coordinated sweaters. There was one Medtronic page that featured a man in a wheelchair who looked like he could’ve been auditioning for the role of “Grandpa Who Offers Life Advice in Act Two.”

I couldn’t even be angry about it because statistically the brochures weren’t wrong. When my pulmonologist sent me to pulmonary rehab years ago, I walked in and instantly felt like the class mascot. Everyone was over seventy. They were lovely, warm, and encouraging—don’t get me wrong—but there I was, standing in a circle of people whose grandkids were older than some of my cousins. They shared stories about Medicare paperwork while I was still mastering how to politely decline invitations to Zumba.

That feeling of being the odd one out never fully went away. It wasn’t just the age difference; it was the loneliness of navigating conditions that very few people my age understood. I didn’t know anyone else managing heart failure and sarcoidosis while still working, creating, dreaming, cooking, and dealing with life’s everyday nonsense. Sometimes it felt like being a rare collectible card nobody knew how to trade. People were kind, but they couldn’t relate, not really. And when you’re sick in a way that doesn’t match your age bracket, the isolation can cling to you like hospital gown static.

But time, as always, marches on. And now something interesting is happening: there are more people like me. More folks in their fifties and sixties dealing with heart failure, lung issues, and autoimmune chaos. More people who don’t fit the old medical brochures, which means maybe the brochures need an update—or maybe we finally fit them. I’m no longer the outlier. I’m not the anomaly. I’m simply one of many walking around with complicated hearts and lungs doing the best they can. There’s comfort in that, a strange kind of companionship, even if I had to grow older to get it.

And truthfully, I find myself hoping for one more thing: that someday I’ll be one of the smiling elders on those medical websites. Not because I want to model cardigans or lean on a cane with charming authority, but because reaching that age would mean I made it. It would mean I survived long enough to become the very image that once made me feel so different. Maybe someday someone younger will see my fictional brochure twin and think, Well, at least I’m not alone.

And that, honestly, would be enough.

If any of this resonates—whether you’re aging into your diagnosis or still trying to figure out where you fit—drop a comment below or hit subscribe. Your voice keeps this community alive, and I’d love to hear your story.

Discover more from Tate Basildon

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.